Home »

Humans like comfort zones. We have a tendency to stick to the familiar and spend time with people like ourselves. But this creates blind spots and, in research, those blind spots could contain the next big breakthrough.

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge is enticing leading experts from across science and engineering to bring fresh perspectives and drive innovations. The aim is to increase the pace of progress and overcome longstanding challenges, so that we find better treatments and a cure for type 1 diabetes as soon as possible.

Fresh thinking to accelerate progress

People with type 1 diabetes are already benefiting from the cross-pollination of ideas between scientific fields. For instance, modern insulin pumps stem from technology originally invented by NASA scientists who were trying to solve the problem of monitoring astronauts’ health as missions sent them further and further into space.

The ambition and boldness of the Grand Challenge has given researchers from across scientific disciplines the opportunity to apply their skills and experience to type 1 diabetes.

Professor Dame Molly Stevens from University of Oxford, is an expert in biomaterials. She explores how materials interact with molecules, cells and tissues in the body and uses this knowledge to design advanced therapeutics and biosensing. In her Grand Challenge project, Professor Stevens is teaming up with stem cell researchers at King’s College London to find innovative ways to improve beta cell replacement strategies. For instance, by developing a protective ‘cage’ for transplanted beta cells.

“I’ve found an incredible synergy with my collaborators, allowing us to leverage the materials designed in my lab to improve the delivery of cell-based therapies for type 1 diabetes. It’s an exciting opportunity to make a real impact in this field! The Grand Challenge’s focus on high-risk, high-reward approaches really aligns with my passion for leveraging cutting-edge science to tackle complex medical challenges.”

Professor Shuomo Bhattacharya’s career has taken him from India where he researched rheumatic fever during his medical training, to studying heart development at Oxford University. But in recent years he’s been thinking about ticks, how they avoid being noticed by the body’s immune system, and how we could harness this system to combat autoimmune diseases.

“[The Grand Challenge] gave me the opportunity to apply stuff that I had discovered in a completely new arena that I had never even thought about. Most people including researchers and funding organisations tend to work in ‘silos’. Including diverse scientific backgrounds in a programme to tackle type 1 diabetes is the first step to break down these silos and bring in fresh ideas. I think the Grand Challenge got this right.”

Dr Tom Piers works with microglia – the immune cells of the brain. His research in this area has ranged from investigations into multiple sclerosis to Alzheimer’s disease progression. In recent years, Dr Piers has become interested applying his skills in diabetes and has been looking for a chance to do so.

“After my colleague Dr Criag Beall outlined the project idea, I have been very excited about the type of science that we can produce, crossing neuroscience, diabetes and cutting-edge biotechnology. But there are very limited funding opportunities for such high-risk high reward research. The Grand Challenge is addressing this and providing unprecedented support for these types of studies.”

Professor Eoin McKinney has primarily focused on immune responses to infections in our bodies. Together with the Grand Challenge, he’s now looking for new drugs that could potentially help prevent type 1 diabetes.

“The nature of research is that we think hard about a problem and become experts in applying particular methods to help solve it. But we also know that big leaps forward often come from applying our methods to a new problem or thinking differently by working with experts in other fields. It’s surprisingly difficult to do this – a side-effect of being focussed on one thing. That’s what excited us about the Grand Challenge.

We are being challenged to think differently and come up with more radical proposals to change the way things are done. This is where science can be most exciting and, hopefully, most productive too.”

A unique opportunity to change lives

Like Professor Bhattacharya who “spent most of that Christmas reading up about type 1 diabetes”, researchers from diverse fields of science are now excited about applying their knowledge and expertise to help people with type 1 diabetes.

Dr Piers, whose wife has type 1, sums it up:

“In my view, working across disciplines and disease areas with a diverse array of researchers is an excellent way of generating new, innovative and paradigm shifting ideas. I think we’re on the cusp of developing some very exciting new technologies to support people with type 1 and a scheme like the Grand Challenge will speed up their impact.”

You may also be interested in

Despite what you learned at school, insulin isn’t just made in the pancreas

June 16, 2025

This article is written by Dr Craig Beall and is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

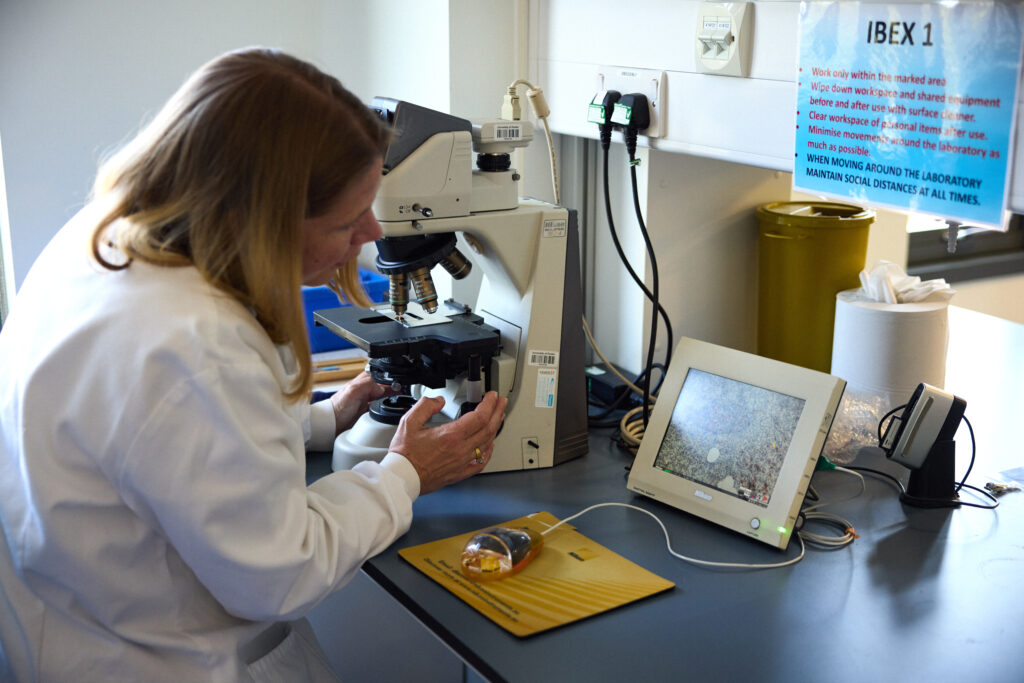

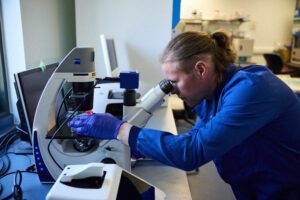

Dr Craig Beall in his research lab

Your brain makes insulin – the same insulin produced by your pancreas. The same insulin that is not produced in people with type 1 diabetes and the same insulin that does not work properly in people with type 2 diabetes.

Scientists have known for over 100 years about insulin producing cells in the pancreas. These spherical islands of cells, called islets, contain insulin producing beta cells.

But we’ve only just started to learn about brain insulin production. The fact that insulin is made there is still largely unknown, even among diabetes scientists, doctors and people with diabetes.

Yet, it was discovered there in the late 1970s – then promptly disregarded.

A study published in 1978 showed the levels of insulin in the rat brain were “at least 10 times higher than that found in plasma … and in some regions … 100 times higher”. If true, why isn’t this more widely known.

Because soon after this discovery, clear evidence showed the transfer of insulin from blood to brain. One study in 1983 measuring insulin in rodent brain said that “insulin found in these extracts was ultimately derived from pancreatic insulin”. They could not find the machinery to process insulin in the brain, at least with the tools available at the time.

This led to the assumption – for nearly the next 30 years – that all brain insulin came from the pancreas.

Insulin can and does move from the blood to the brain. But local sources of insulin are produced in specific places to do specific things.

The brain cells that make insulin

First, what is surprising about brain insulin production is that there is not one but at least six types of insulin-producing brain cell. Some have been confirmed in both rodent and human brain, others currently just in rodents.

One of the first brain cells shown to make insulin is the neurogliaform cell. These live in a brain area important for learning and memory. Most surprisingly, the production of insulin here depends on the amount of glucose present – a feature shared with pancreatic beta cells.

Its not clear what this insulin source does. Based on the location, it may contribute to cognitive function.

This area also has cells that create new neurons throughout life, called “neural progenitors”. These cells also make insulin.

A similar cell from the olfactory bulb, the processing centre for smell, also has insulin-producing progenitors. What insulin does here is still unknown.

But one insulin producing brain cell might regulate growth. A 2020 study showed that insulin is made and released from stress-sensing neurons in the mouse hypothalamus. This is a brain area that controls growth and metabolism. It also has the highest insulin levels in the human brain.

The researchers showed that stressing mice caused hypothalamic insulin production to decrease. This led to poorer growth in the animals. In the case of mice, their bodies were shorter.

Hypothalamic insulin maintained growth hormone levels in the pituitary gland. This is sometimes called the master gland as its involved in making or controlling production of other hormones. Having less local insulin meant less growth hormone production.

Then there is the choroid plexus. This is the brain region that makes cerebrospinal fluid. In humans, that is about half a litre of this clear colourless liquid every day.

Cells lining the choroid plexus – the epithelial cells – make a nourishing broth of growth factors and nutrients to keep the brain healthy. Only recently was insulin production found here in mice.

The choroid plexus secretes fluid directly into brain ventricles, the spaces deep inside the brain. This fluid flows around the whole brain, perhaps delivering insulin more widely.

One place it does travel to is the appetite control centre in the hypothalamus.

A 2023 study in mice showed that genetic control of insulin production by the choroid plexus could change food intake. The hypothalamus was rewired by changing choroid plexus insulin levels. Insulin released from here suppressed appetite.

Another source of insulin in the brain also reduces food intake. A 2022 found that insulin producing neurons at the back of the brain, called the hindbrain, reduced food intake in mice.

Might help the brain stay healthy as we age

So if brain insulin can change appetite, does it control blood sugar?

No. At least there is no evidence for this currently. It is unlikely this insulin leaves the brain. Therefore, its unlikely to control glucose levels in the same way.

Instead, insulin in the brain might help the brain stay healthy as we age. For example, Alzheimer’s disease is often, unofficially, termed type 3 diabetes. This is because the brain is insulin resistant in Alzheimer’s. It cannot properly use glucose either.

This is a big problem. Glucose is the main fuel for the brain. In fact, estimates suggest there is a 20% energy gap in Alzheimer’s. Even without brain cell loss, this alone will impair cognitive performance.

This has led to attempts to boost brain insulin. Spraying insulin into the nose can improve cognitive performance in Alzheimer’s, in some, but not all studies.

Brain glucose use also decreases over time and intranasal insulin also seems to limit this decrease.

Therefore, is more brain insulin always a good thing?

Not necessarily. In women specifically, higher levels of insulin in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with poorer cognitive performance.

There is still much to learn about brain insulin production. For example, which insulin source came first? The brain or the beta cell? Hopefully it doesn’t take another 30 years to find out.

But given the strength of evidence of brain insulin production, it won’t be long until our school textbooks are updated.

Read more about the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge project led by Dr Craig Beall and Dr Thomas Piers that looks at how to make use of brain insulin production to improve beta cell therapies.

Viral triggers, ticks to tackle the immune system and a smart coat for insulin: Latest type 1 diabetes research

May 27, 2025

At the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge, we support cutting-edge research aimed at bringing us closer to better treatments, and potentially, a cure. The research teams we fund are leaders in the field and their latest discoveries, highlighted here, are contributing to global efforts to transform the treatment of type 1 diabetes.

Connection between a common virus and type 1 diabetes

The development of type 1 diabetes is caused by a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, which trigger the immune system to turn on and destroy insulin-producing beta cells. The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge is investing in research to learn more about precisely what goes wrong and how this process unfolds.

An international research team, including our Senior Research Fellow Professor Sarah Richardson, has just published the strongest evidence to date that enteroviruses play a role in the development of type 1 diabetes.

They studied pancreas samples from nearly 200 donors to check for signs of enterovirus infections. These included samples from people with and without type 1 diabetes, as well as individuals who had type 1 diabetes autoantibodies – early immune warning signals that indicate a high risk of developing the condition in the future.

They reported that signs of enterovirus infection were most common in people with type 1 diabetes who still had some functioning beta cells. Infections were also present in people with autoantibodies, but much less common in those without diabetes or in people with type 1 whose beta cells had already been completely destroyed.

A key finding was the presence of a protein made by the enterovirus, called VP1. The researchers found VP1 was strongly linked to high levels of HLA class I molecules. These are markers of an early immune system response in the pancreas. This is the first time these viral and immune markers have been found together – including in the early stages of type 1 before a diagnosis.

These findings offer the strongest evidence to date that enteroviruses may trigger or accelerate the onset of beta cell destruction in early type 1 diabetes. A clearer understanding of their role could lead to new approaches that target the immune processes they influence — potentially slowing or even preventing type 1.

‘Ticking’ beta cell protection

One part of a solution to curing type 1 diabetes is to transplant beta cells, either donated or grown in labs, into people with type 1 so they could produce their own insulin again. However, the immune system is primed to attack the new cells too. This happens partly because the transplanted cells release chemokines—chemical signals that attract immune cells. Blocking these signals is difficult, as there are many different types.

Scientists have discovered that ticks produce proteins called evasins that can block several of these signals at once. Professor Shoumo Bhattacharya’s team has studied these evasin proteins and identified the specific peptides that have this powerful blocking ability. They’ve established a new method that allows them to test many versions of these peptides rapidly, and pinpointed those that work best at calming the immune response.

Published in Communications Biology, these innovative findings lay the groundwork for Professors Shoumo Bhattacharya and David Hodson’s Grand Challenge project. They aim to use these peptides to help protect new beta cells from immune attack after being transplanted. This could create a safer alternative to immunosuppressive drugs and improve the success of beta cell therapies for type 1 diabetes.

Giving insulin a smart coat

Professor Zhen Gu’s team at Zhejiang University in China has developed a new insulin delivery system, called i-crystal, as reported in their latest publication in Nature Nanotechnology.

Designed to help people with type 1 diabetes keep blood sugar levels within target range, the system uses specially coated insulin crystals that release insulin slowly and steadily. The coating is a unique membrane that enables the crystals to respond precisely to changes in blood sugar and ketone levels. This means insulin is only released when blood sugar levels rise and stops when it drops, helping people with type 1 avoid highs (hypers) and lows (hypos).

Early tests show that i-crystal could help regulate blood sugar levels for over a month in mice after just one injection, and for more than three weeks in minipigs after five daily doses. This suggests this delivery system could reduce the need for frequent injections and make daily diabetes management easier.

If successful, i-crystal could offer a safer, longer-lasting, and more adaptable form of insulin therapy for people living with type 1 diabetes.

What are beta cell therapies, and do they offer hope for a cure for type 1 diabetes?

April 15, 2025

Clinical trials in beta cell replacement are creating a buzz among the diabetes community. We explain what beta cell therapies are, how close they could be to becoming a potential treatment option, and how Grand Challenge research is helping bring them closer to the reality.

In type 1 diabetes, the immune system attacks the beta cells in the pancreas, which make insulin. Insulin is essential for regulating our blood sugar levels. So people with type 1 have to check blood sugar and take insulin multiple times a day, every day, to stay alive.

For many people, the advances in diabetes technologies mean that some of this constant checking and dosing can now be done automatically by continuous glucose monitoring and hybrid closed loop systems. However, even the latest tech cannot get close to mimicking the body’s finely tuned system for keeping glucose in check.

One of the most promising routes to a cure for type 1 diabetes is to seek ways to replace the lost beta cells and restore insulin production. We know it can work – the first successful human transplants of beta cells taken from a donor happened as far back as 1990.

The parts of the pancreas that contain beta cells are known as islets. In 2008, the UK launched an islet transplant programme for people with type 1 diabetes who experience frequent life-threatening episodes of low blood sugars (severe hypoglycaemia, or ‘hypos’) but have no awareness of the warning signs. It was an exciting advance, offering the hope of freedom from insulin therapy for some.

Islet transplants are limited

While islet transplants are pretty effective at giving people more stable blood sugar levels and cutting episodes of dangerous lows, there are several reasons why they’re not widely suitable as a treatment for type 1:

- Data suggests that an average of 3 donor pancreases are needed for 1 successful transplant. Donor organs are sourced from deceased individuals and – like most transplant programmes – the demand severely outweighs the supply of usable tissue.

- Transplants from a donor may be rejected by the body, so recipients must take lifelong medication to suppress their immune system (immunosuppressants). This leaves people compromised – at greater risk of certain cancers and severe infections.

- Despite immunosuppression, transplanted islets often fail to survive in the long term because they can’t get the oxygen and nutrients they need.

- While they can allow some people to temporarily stop insulin therapy, this is rarely permanent. Over time, most people will need insulin again, although usually at lower doses.

Fewer than 350 islet cell transplants took place in the UK between 2008 and 2022. There’s an urgent need to find effective and sustainable alternative approaches to beta cell replacement that can be accessed by many more people with type 1. That’s why beta cell replacement is one of the three major research themes of the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge.

Exciting trials underway

Some of the most talked-about research happening in type 1 diabetes right now are clinical trials in beta cell replacement.

One trial, led by a company called Vertex, is testing transplants of beta cells grown in the lab. The results have been really promising, with some participants no longer needing insulin. However, they still need powerful immunosuppressants to prevent rejection. The treatment is now in the final phase of testing, and if all goes well, Vertex plans to seek global approval in 2026. It’s likely this would initially only be for people who experience frequent severe hypos and have no hypo awareness.

In October 2024, Chinese researchers reported positive results using beta cells grown from a patient’s own stem cells. It’s very early days – they only tested it in one person – but this approach has potential to overcome the rejection problem because the transplanted cells would be recognised as ‘self’.

Another first-in-human study was reported by Sana Biotechnology at the start of 2025. They used donor beta cells but gene-edited them to become invisible to the immune system. After four weeks the transplanted cells had avoided immune attack and were producing insulin.

The bigger picture

Type 1 diabetes is complex and we’re unlikely to land on a one-size-fits-all cure. So, while the current trials are hotly anticipated, they’re only one part of the story. And that’s why the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge is funding over £16 million into 10 research projects looking at building better beta cells for transplantation, protecting beta cells during and after transplantation and regrowing beta cells in people with type 1 diabetes.

Nearly two decades after the islet transplant programme launched in the UK, we’re getting closer to better beta cell replacement therapies. And the Grand Challenge is helping to push the pace of progress so that more people can be released from the daily burden and dangerous complications of type 1 diabetes.

You may also be interested in

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge makes waves at DUKPC

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge took centre stage at this year’s Diabetes UK Professional Conference, uniting researchers and people affected by type 1 diabetes to share their expertise and celebrate progress with the wider diabetes community.

March 14, 2025

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge took centre stage at this year’s Diabetes UK Professional Conference, uniting researchers and people affected by type 1 diabetes to share their expertise and celebrate progress with the wider diabetes community.

Our community in the spotlight

The main Grand Challenge session was a powerful showcase of our ever-growing community, featuring 13 new projects we’ve funded in the last year.

The session began with updates from researchers working to build better beta cells in the lab from stem cells, protect new cells during and after transplantation, and regrow beta cells in people with type 1 diabetes.

Later on in the conference, we heard more about islet transplantation, using cells from donor pancreases. Prof Shareen Forbes discussed the potential of microparticle drug delivery to protect transplanted islets and improve their survival. And we were joined by Dr Vicky Salem who highlighted innovations in biomaterials that could transform islet transplantation.

Our immune insights project leads shared exciting progress on targeting the type 1 immune system attack in safer and more effective ways. Dr James Pearson revealed that some immune cells follow a daily rhythm, and that’s why his project is testing if immunotherapies timed to these cycles will improve their effectiveness.

We also welcomed Profs Michael Weiss, Matthew Webber and Zhiqiang Cao, who discussed their eye-opening ideas to develop novel insulins that could act more quickly and precisely, ultimately reducing the burden of type 1 diabetes management.

Picture of Profs Michael Weiss, Matthew Webber accepting their awards; credit: © Julie Broadfoot

You can find more details about each project presented at DUKPC on our funded projects page.

Lived experience at the heart of research

A dedicated session at DUKPC highlighted how the quality and impact of Grand Challenge research is being enhanced by meaningfully involving people with lived experience of type 1.

Heather Robinson, a Together Type 1 young leader, shared striking statistics on the difficulties of transitioning from paediatric to adult diabetes care, underscoring the need for greater involvement from those directly affected.

Dr James Pearson echoed this, sharing how the challenge of recruiting young adults with type 1 for research led him to involve them more actively through the Cardiff Diabetes Innovation Committee. Committee members reflected on how this engagement deepened their understanding of type 1 diabetes and ensured research truly benefits those who need it most.

Picture of Dr James Pearson and Lilly from the Cardiff Diabetes Innovation Committe; credit: © Philippa Gedge Photography

Recognising the importance of lived experience in research, Professor Sean Dinneen spoke about working with young adults with type 1 to identify gaps in care and improve treatments, while Dr O’Donnell showcased his project co-developing user-led technology that prioritises real-life experiences and emotional well-being.

Amelia Burke, a glass artist from Wales and mum of Ruby who lives with type 1, emphasised that involvement must be accessible and approachable. Her interactions with Grand Challenge researchers inspired her to use artistic methods to represent her daughter’s experience and raise awareness about beta cell therapies.

Heather shared her experience at the conference with us:

“Getting to experience DUKPC from multiple perspectives was such a unique and unforgettable opportunity. From interviewing researchers, speaking on a panel, meeting other Young Leaders from the Together Type 1 program and presenting in the Grand Challenge Patient and Public Involvement session, it was a jam-packed few days! Being able to watch the involvement of experts by experience increase over the past few years has been brilliant, and with the collaboration of Steve Morgan Foundation, Diabetes UK and Breakthrough T1D has only developed this. Speaking with researchers and experts by experience brought such a broad range of viewpoints and I’m so excited for the future of patient-led diabetes research and healthcare.”

Picture of Heather with Dr Craig Beall at DUKPC

Bringing research to reality

For research to truly make an impact, scientific breakthroughs must be translated into real-world solutions. And that’s exactly what we’re aiming to achieve through the Grand Challenge— accelerating great ideas to change the lives of those affected by type 1 diabetes. As part of this, we hosted a ‘Top Tips on Commercialisation’ session, bringing together experts in research funding, policy, and entrepreneurship to share practical advice on turning research into real-world impact. This is just the beginning —throughout this year we’ll continue to support our community in in moving innovations from the lab into people’s lives.

Dr Andy Chapman, CEO and Co-Founder of Carbometrics says:

“Thank you to Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge for inviting me to speak at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference 2025 in Glasgow. It was a privilege to join such an esteemed panel to discuss the challenges and future of commercialisation in diabetes technology, and connect with fellow innovators in this space.”

Dr Bethany Cragoe, Charity Business Manager of LifeArc, says:

“Charities are crucial in getting research to patients by leveraging the expertise of many stakeholders including patients, scientists, clinicians, and industry partners. Technology transfer is key in this process, and early engagement with technology transfer offices helps develop effective intellectual property strategies and potential routes to patient benefit.

“Researchers should understand the translational pathway and plan early to ensure their work benefits patients. Building strong networks with industry and funders is key to success in this journey. Organisations and initiatives such as Knowledge Exchange UK, Innovate UK and Association of Technology Transfer Professionals can support this. All these elements must come together to ensure that the funded research outputs are able to realise their maximum potential for patient benefit.”

Picture of Dr Bethany Cragoe speaking at the ‘Top Tips on Commercialisation’ credit: © Philippa Gedge Photography

From discovery to innovation: 103 years of insulin progress

March 4, 2025

11 January 2025 marked exactly 103 years since insulin was first given to a person with type 1 diabetes, a 14-year-old boy called Leonard Thompson. At the time, a type 1 diagnosis was a death sentence and before receiving insulin, Leonard Thompson’s blood sugar levels were dangerously high.

The history of insulin is one of scientific breakthroughs, perseverance, and innovation.

Banting and Best’s breakthrough

The breakthroughs began in 1921 when Canadian researchers Frederick Banting and Charles Best discovered that the hormone insulin could control blood sugar levels and was essential for our body to make and use energy. This discovery was a turning point for people with type 1 diabetes, as it became clear that supplying the insulin they need could be life-saving.

Banting, Best, and their colleague John Macleod were able to extract insulin from the pancreas of dogs but needed the help of biochemist James Collip in purifying the insulin so it would be safe enough to be tested in humans. In December 1921, a more concentrated and pure form of insulin was developed, this time from the pancreases of cattle.

Evolution of insulin extraction

The production of insulin, initially from animal pancreases, became more widespread in the following years, marking the beginning of modern type 1 diabetes management. By late 1923, insulin was commercially available, and people with type 1 diabetes could live longer, healthier lives with effective treatment.

In the decades that followed, innovations continued. In the 1970s, synthetic human insulin produced using bacteria cells replaced insulin from animal sources. This allowed for a more consistent and efficient supply of insulin. The 1980s saw the development of long-acting and rapid-acting insulins, improving control over blood sugar levels.

Innovations in insulin

Research into insulin has continued to evolve. Recent advancements have led to better ways of taking insulin, with the creation of insulin pumps and hybrid closed loop technologies that can help give people with type 1 diabetes the amount of insulin they need automatically and more precisely. Insulin remains the backbone of type 1 diabetes management today with everyone living with type 1 still relying on insulin to manage their condition, just like Leonard Thomson in 1922. Although we’ve come a long way since then, insulin treatment remains difficult and demanding. Insulins need to be easier, smarter and safer.

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge and novel insulins

To get there, the Grand Challenge is funding researchers to continue to write the story of insulin. They’re working to design new types that will work quicker and more precisely, often called novel insulins.

We’ve invested £2.7 million so far to fast-track discoveries in three different avenues:

- Ultra-rapid insulins that would respond more quickly to rising blood sugars, reducing spikes and bringing a fully closed loop system closer.

- ‘Smart’ glucose-responsive insulins would activate when blood sugar levels are high and deactivate when it drops too low. This could make insulin management more automatic, reducing the constant need for calculations or frequent injections and reducing the risk of lows and highs.

- Combining insulin with another hormone that raises blood sugar levels.

This could give people more stable levels, making daily management easier and more effective. Ultimately, the goal is to make insulin treatment feel less like a full-time job and more like something that works in the background – giving people with type 1 diabetes more freedom and better health.

You can find out more about these projects in the ‘Novel Insulins Innovation Incubator’ section of our funded projects page.

New funding available to boost beta cell research in the UK

December 20, 2024

We’re launching a new funding call to address the limited availability of stem cell-derived beta cells for research purposes.

The aim is to facilitate more high-quality research into beta cell therapies, speeding up progress towards a cure for type 1 diabetes.

To achieve this, we’ve partnered with the Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute (ARMI), the US leading organisation in manufacturing cells, tissues and organs.

Funding is available for UK-based researchers to test if stem cell-derived beta cells produced by ARMI can survive shipment from the US to the UK. And if they can, whether they work as expected in both lab studies and living organisms.

We’re inviting UK experts with a track record of producing and testing stem cell-derived beta cells to apply for funding to test ARMI’s beta cells. Funding is available for up to three sites across the UK.

Successful researchers will also have the opportunity to directly compare ARMI’s beta cells with their own lab-made beta cells. This may help them to improve their own production process and identify the most effective product for wider rollout.

The hope is that it will enable the development of a reliable supply of high-quality, pre-made stem cell-derived beta cells for use by UK scientists. By saving researchers time and ensuring consistency across studies, this initiative is expected to accelerate the development of new beta cell replacement therapies.

Apply for funding

Details about the call can be found here. You’ll need to submit your application by 31 January 2025.

If you’re interested in applying, we strongly encourage you to attend our funding call webinar on 8 January 2025 at 14:00 GMT and reach out to the T1DGC Research Funding Team to discuss the opportunity further (smfgrandchallenge@diabetes.org.uk).

The Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute (ARMI | BioFabUSA) said:

“ARMI is proud to partner with the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge to advance beta cell research. By providing high-quality, stem cell-derived beta cells for validation, we aim to accelerate breakthroughs in type 1 diabetes treatment and improve the scalability of regenerative therapies. This initiative represents a critical step in bridging global efforts to bring innovative solutions to patients.”

Professor Matthias Hebrok, Vice Chair of the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge Scientific Advisory Panel, said:

“Testing stem cell derived islets produced by a foundry for their functional properties upon being sent to the UK is critical to ensure high quality tissues will be available to accelerate research in type 1 diabetes.”

Gaining pace towards a cure – a round-up of 2024

December 16, 2024

The global quest to create better treatments and find ways to prevent and cure type 1 diabetes continued to gather pace in 2024. At the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge, we kickstarted 10 pioneering research studies across the UK and globally, expanding our portfolio of funded science to 19 projects, involving 161 researchers in 47 institutions across 8 countries, and shared our mission with thousands affected by the condition.

Here, we round-up the highlights of the year.

Science fiction into fact

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge is taking the quest to cure type 1 diabetes to a new level by emboldening scientists to be innovative and disruptive, leading to totally new avenues of discovery. That’s why some of the projects funded in 2024 read like sci-fi storylines, from investigating insulin-producing brain cells to copying the immune evasion tactics used by ticks.

This year, we invested over £2 million into four new research projects to tackle the root causes of type 1 and replace the insulin-making beta cells lost in type 1. Four research teams are now hard at work on these innovative ideas, and others.

Dr Elizabeth Robertson, Director of Research at Diabetes UK, said: “These high-risk, high-reward, innovative projects exemplify the transformative potential of the research funded by the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge. By driving forward bold, cutting-edge approaches, we’re stepping closer to revolutionising the way type 1 diabetes is treated and improving the lives of those affected by the condition.”

One of the newly funded researchers, Dr Craig Beall, summed up the ambition: “The moonshot we’re aiming for is a cure that frees people with type 1 diabetes from insulin injections and immunosuppression.”

Innovating insulin

For over a century, type 1 diabetes has been treated with insulin. It’s a life-saving treatment, but it’s also a very blunt instrument, unable adapt to the wide-ranging factors that affect blood glucose levels.

In August 2024, we invested over £2.7 million into six projects to develop ‘smart’ insulins that could transform the treatment of type 1. The six research teams are aiming to create next-generation insulins that can respond to changing blood glucose levels, ultrafast-acting insulins and a combination drug that can both raise and reduce glucose levels.

Rachel Connor, Director of Research Partnerships at Breakthrough T1D, said: “Managing glucose levels with insulin is really tough, and it’s time for science to find ways to lift that burden. By imagining a world where insulins can respond to changing glucose levels in real-time, we hope these six projects will help to create that new reality, relieving people with type 1 of the relentless demands that living with this condition places on them today.”

On tour with the Grand Challenge

People affected by type 1 diabetes are at the heart of the Grand Challenge. It was born out of Steve and Sally Morgan’s family experience of type 1, and we actively involve those living with type 1 diabetes at every stage of the research process — from shaping funding decisions to playing a crucial role in supporting researchers in delivering their projects.

So, in 2024, we took the Grand Challenge into the community, talking to thousands of people who understand the day-to-day struggle of type 1 and the importance of our mission to revolutionise treatments and find cures.

We were delighted to join DiabetesChat’s fifth virtual research event, and to attend the Talking About Diabetes (TAD) event in Liverpool. At TAD 2024, Liam Eaglestone, CEO of the Steve Morgan Foundation, and his son Jack, took to the stage to talk about their experiences of living with type 1. Liam said: “[Diabetes] Technology is great – but it is not a cure. The Grand Challenge is seeking that cure, by bringing together some of the best and brightest brains in the type 1 research community.”

We were joined at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference by seven Young Leaders from the Together Type 1 programme. These inspiring young advocates interviewed Grand Challenge researchers and shared their experiences of living with type 1 with scientists and healthcare professionals. And in November, some of the Grand Challenge team visited Northern Ireland to give the Together Type 1 Young Leaders there an update on the latest research developments.

Young Leader Elisa Featherstone said: “Hearing about this research programme made me consider, for the first time, the reality of not having type 1 diabetes for the rest of my life. A cure may be sooner than we think, and it may well be because of the Grand Challenge!”

Progress through collaboration

Collaboration is key to progress, a principle exemplified at our first Beta Cell and Root Causes symposium held in November 2024. The symposium brought together hundreds of researchers from different strands of the Grand Challenge and people living with type 1 diabetes.

Dr Mirjam Eiswirth, who lives with type 1 diabetes and wrote a summary of the symposium, said: “Personally, I am very excited about the progress we’ll make through these research projects. They have the potential to change the lives of millions of people with type 1 diabetes for the better.”

Simon Heller, Chair of the Scientific Advisory Panel, said: “We’re moving faster than I thought we would. The willingness of scientists to collaborate shows what can be achieved when we work together.”

At the symposium, the first recipients of Grand Challenge funding, our Senior Research Fellows Professor Sarah Richardson, Dr James Cantley and Dr Victoria Salem, highlighted the remarkable progress their projects have made over the past year. Early career researchers in Dr Cantley’s lab have taken pancreatic cells from mice and regrown them into beta cells – they will now search for drugs that can support this process. Professor Richardson’s team has found that small clusters of beta cells, common in young children, are more vulnerable to the autoimmune attack. Lastly, researchers in Dr Salem’s team is engineering a device that can protect lab-grown beta cells from the immune attack while providing nutrients via a blood supply. We’re excited to track the the trio’s progress in 2025!

Looking ahead with hope

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge will continue to build momentum in 2025. We’ll begin to see early outcomes from our first projects and will invest in more disruptive and collaborative science.

Building on the conversations sparked at the symposium, we look forward to the Grand Challenge advancing through collaborative working, and we’re excited to continue this progress at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference in February, where Grand Challenge researchers will share ideas and forge new connections.

As Sally and Steve Morgan said: “It’s about doing things differently, it’s about taking risks, but above all it’s about collaboration. Let’s work as a team.”

The Grand Challenge community – “Work differently, work collaboratively, work swiftly”

December 4, 2024

In November, we hosted our Beta Cell Therapy and Root Causes Symposium, uniting the rapidly growing Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge community. More than 100 researchers, people with lived experience of type 1 diabetes, and collaborators came together for the first time. It was a space to share progress and fresh ideas, and to explore new collaborative opportunities, leveraging the diverse expertise within the community. Importantly, we also got to hear how people affected by type 1 diabetes have been working with research teams to ensure the discoveries and treatments scientists pursue are grounded in their needs.

Dr Mirjam Eiswirth, who lives with type 1 diabetes and leads the Patient and Public Involvement activities for Prof Shareen Forbes and Dr Lisa White’s project, was one of our speakers. Here, she shares her thoughts on the symposium.

“£50 million – that’s the incredible amount of money that the Steve Morgan Foundation has dedicated to the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge towards the race for a cure. It’s a marathon, not a sprint, but as we heard at the Symposium – we’re well on track.”

Mirjam speaking at the symposium

A meeting of minds

107 experts from 27 institutes across 8 countries and nations gathered in London for the first time to focus on two of the Grand Challenge’s strands:

- Root causes of type 1 diabetes: what is it that makes the immune system attack the pancreas, and how can we stop this?

- Replacing beta cells: once the beta cells have been destroyed, how can we replace them with new, functioning ones to give the body a chance to make insulin again?

Can we restore insulin production in the body?

We heard about innovative approaches Grand Challenge researchers are exploring to make beta cell transplants better, more efficient, and have fewer side effects. Or to even help existing healthy pancreatic cells morph into beta cells, so that the body can produce its own insulin again. Because, as Sarah Gatward, one of the experts by experience, so neatly put it: “Nothing can control blood glucose better than beta cells.”

Could we stop type 1 diabetes from developing?

The second key theme was understanding what happens in the body that makes it turn against itself and destroy beta cells in type 1 diabetes. If we could stop this immune attack early and protect the beta cells, we could potentially stop type 1 diabetes from developing at all.

Grand Challenge teams told us about the innovative ways they’re hoping to do this, and some of the challenges to tackle along the way. We’d need to catch people early on the path to type 1 diabetes, which means we need good ways to screen for it. And we’d need to make sure we only stop the specific immune reaction at the root of type 1 diabetes, rather than suppressing the whole immune system.

Putting people with lived experience at the centre of the Grand Challenge

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge models the collaborative and disruptive spirit it champions: By including people with the lived experience from the get-go and every step on the way.

Several experts by experience, including myself, gave updates on the different ways we’re getting involved, including reviewing research proposals, as patient and public involvement co-investigators, and as sounding boards when it comes to the applicability of any novel therapy the scientists develop. Because we can ask those uncomfortable “so what” questions or say, “this therapy only makes sense to me if it helps me for more than a year or two – it needs to be a proper cure”.

For the researchers in the room, hearing more about our involvement, perspectives, and why they matter was invaluable. Dr Craig Beall, lead researcher, said: “Hearing the voices of experts by experience was inspirational and at times emotional.”

Anonymous feedback also reflected this:

Expert by experience: “I felt I was able to help inform researchers and others of what their research means to those living with type 1 diabetes and I feel confident that my input has been taken on board and will be used to influence what they do and how they present their research. ”

Early-career researcher: “I met several experts by experience and it really hammered home the importance of our research. I was astounded by the incredible role experts by experience played in shaping grant applications and steering research objectives.”

Experts by experience talking about involving people living with type 1 diabetes at the symposium

Many perspectives, lively debates

Senior researchers, early career researchers, and not least people with lived experience of type 1 diabetes shared their thoughts, hopes and projects related to the Grand Challenge. What unites us all is the vision of creating a world where diabetes can do no harm – and to be creative, think out of the box, work collaboratively, and work swiftly.

One researcher summed it up: “It felt like a community, which was great.”

Delegates chatting at the symposium

Looking ahead

Personally, I am very excited about the progress we’ll make through these research projects. They have the potential to change the lives of millions of people with type 1 diabetes for the better. A cure is still years, if not decades away – the journey to breakthroughs is a long and complex one. We need to move from discoveries in the lab, to testing new treatments with people in clinical trials, to ensuring widespread access to cures. But it’s a path filled with incredible moments of innovation and hope. And I find myself just as excited for the journey as the destination.

Researchers, practitioners and experts by experience working closely together, driven by shared ambition, can really make a difference.

You may also be interested in

Four innovative projects receive funding from the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge

October 22, 2024

We’re investing over £2 million into four new research projects exploring creative approaches to improve beta cell therapies and tackle immune system dysfunction in type 1 diabetes.

The latest batch of cutting-edge projects are now underway thanks to funding from the Grand Challenge. This investment will help research teams across the UK to test their original and potentially groundbreaking ideas on ways to improve the function and survival of insulin-producing beta cells and keep the type 1 immune attack at bay. Together, these pioneering projects offer new hope to improve the lives of people with type 1 diabetes.

Tiny molecules with big potential

Dr Aida Martinez-Sanchez, Dr Prashant Srivastava and their team at Imperial College London, along with Dr Teresa Rodriguez-Calvo at Helmholtz Zentrum Munich, will study how microRNAs – tiny molecules in our cells that switch different genes on and off and change how the cell works – affect the function and survival of beta cells.

Dr Aida Martinez-Sanchez said:

“The complex methodologies we’re developing have the potential to form the basis of future research in other important aspects of beta cell biology, such as how to reduce the risk of transplant rejection, or delay or prevent beta cell destruction in type 1 diabetes.”

Read more about the team’s project.

Insulin on the brain to outsmart type 1

At the University of Exeter, a team led by Dr Craig Beall and Dr Thomas Piers will explore whether a type of brain cell that produces insulin can be used to develop long-lasting, effective beta cell therapies for type 1 diabetes which are resistant to the type 1 immune attack.

Dr Craig Beall said:

“The moonshot we’re aiming for is a cure that frees people with type 1 diabetes from insulin injections and immunosuppression, and this is the next step in that journey.”

Read more about the team’s project.

Developing drugs from bugs – how do beta cells tick?

Tick saliva contains peptides that helps to hide them from their victims’ immune systems. Researchers at the University of Oxford led by Professor Shoumo Bhattacharya and Professor David Hodson will harness these immune system evading peptides to develop beta cell therapies that are protected from the type 1 immune attack. This could transform the way the condition is treated by helping people to make their own insulin again without the need for immunosuppressive drugs.

Professor Shoumo Bhattacharya said:

“Our lab is looking to nature for new ways to treat inflammatory diseases. We aim to develop tick-inspired treatments to help people with type 1 diabetes, which could improve the success of beta cell transplants.”

Read more about the team’s project.

Could an existing medicine reverse the steps that lead to type 1 diabetes?

Professor Eoin McKinney and his team at the University of Cambridge will use genetic insights and powerful machine learning technology to identify and test new drug candidates for type 1 diabetes. The team has created detailed maps of immune cell changes in people at high risk of type 1, identifying specific genetic patterns, called signatures, that are only seen in those who develop the condition. Using these signatures, they now aim to understand the abnormal immune signals that lead to type 1 diabetes and find drugs to counter them, with the aim of preventing the condition from progressing.

Professor Eoin McKinney said:

“By selecting candidate treatments rationally based on a match with type 1 data, we will stand the best possible chance of finding a safe and effective approach to stop the condition with real impact for patients everywhere.”

Read more about the team’s project.

Dr Elizabeth Robertson, Director of Research at Diabetes UK, said:

“These high-risk, high-reward, innovative projects exemplify the transformative potential of the research funded by the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge. By driving forward bold, cutting-edge approaches, we’re stepping closer to revolutionising the way type 1 diabetes is treated and improving the lives of those affected by the condition.”

Rachel Connor, Director of Research Partnerships at Breakthrough T1D UK, said:

“With these new projects the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenges is now funding a total of 19 innovative research studies, all driving us closer to transforming life for people type 1 diabetes. Each project takes a unique approach to the three challenges in type 1 diabetes that we’re tackling: replacing beta cells, uncovering the root causes of type 1, and developing the next generation of insulins.”