This article is written by Dr Craig Beall and is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

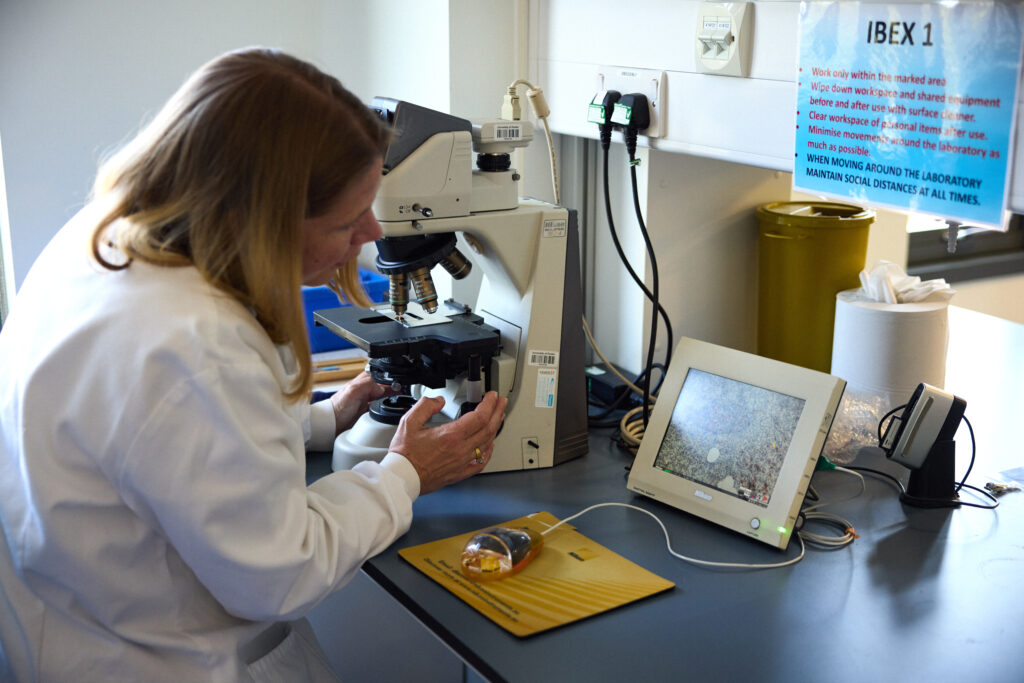

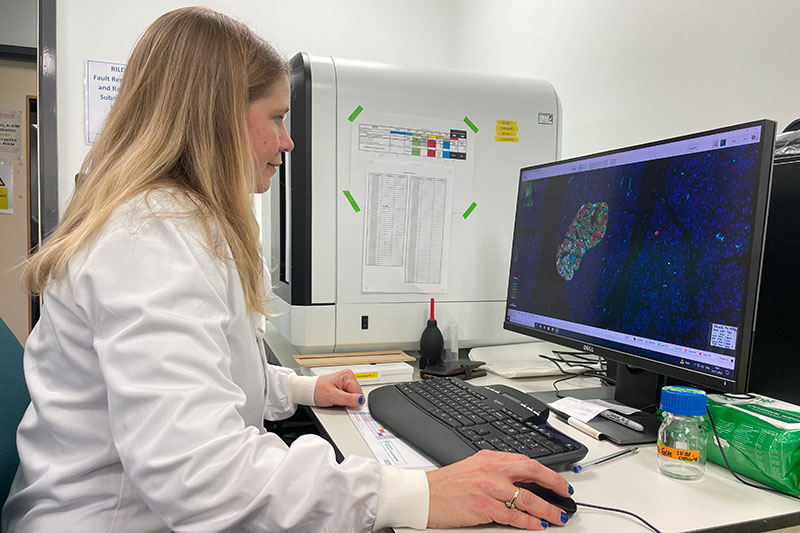

Dr Craig Beall in his research lab

Your brain makes insulin – the same insulin produced by your pancreas. The same insulin that is not produced in people with type 1 diabetes and the same insulin that does not work properly in people with type 2 diabetes.

Scientists have known for over 100 years about insulin producing cells in the pancreas. These spherical islands of cells, called islets, contain insulin producing beta cells.

But we’ve only just started to learn about brain insulin production. The fact that insulin is made there is still largely unknown, even among diabetes scientists, doctors and people with diabetes.

Yet, it was discovered there in the late 1970s – then promptly disregarded.

A study published in 1978 showed the levels of insulin in the rat brain were “at least 10 times higher than that found in plasma … and in some regions … 100 times higher”. If true, why isn’t this more widely known.

Because soon after this discovery, clear evidence showed the transfer of insulin from blood to brain. One study in 1983 measuring insulin in rodent brain said that “insulin found in these extracts was ultimately derived from pancreatic insulin”. They could not find the machinery to process insulin in the brain, at least with the tools available at the time.

This led to the assumption – for nearly the next 30 years – that all brain insulin came from the pancreas.

Insulin can and does move from the blood to the brain. But local sources of insulin are produced in specific places to do specific things.

The brain cells that make insulin

First, what is surprising about brain insulin production is that there is not one but at least six types of insulin-producing brain cell. Some have been confirmed in both rodent and human brain, others currently just in rodents.

One of the first brain cells shown to make insulin is the neurogliaform cell. These live in a brain area important for learning and memory. Most surprisingly, the production of insulin here depends on the amount of glucose present – a feature shared with pancreatic beta cells.

Its not clear what this insulin source does. Based on the location, it may contribute to cognitive function.

This area also has cells that create new neurons throughout life, called “neural progenitors”. These cells also make insulin.

A similar cell from the olfactory bulb, the processing centre for smell, also has insulin-producing progenitors. What insulin does here is still unknown.

But one insulin producing brain cell might regulate growth. A 2020 study showed that insulin is made and released from stress-sensing neurons in the mouse hypothalamus. This is a brain area that controls growth and metabolism. It also has the highest insulin levels in the human brain.

The researchers showed that stressing mice caused hypothalamic insulin production to decrease. This led to poorer growth in the animals. In the case of mice, their bodies were shorter.

Hypothalamic insulin maintained growth hormone levels in the pituitary gland. This is sometimes called the master gland as its involved in making or controlling production of other hormones. Having less local insulin meant less growth hormone production.

Then there is the choroid plexus. This is the brain region that makes cerebrospinal fluid. In humans, that is about half a litre of this clear colourless liquid every day.

Cells lining the choroid plexus – the epithelial cells – make a nourishing broth of growth factors and nutrients to keep the brain healthy. Only recently was insulin production found here in mice.

The choroid plexus secretes fluid directly into brain ventricles, the spaces deep inside the brain. This fluid flows around the whole brain, perhaps delivering insulin more widely.

One place it does travel to is the appetite control centre in the hypothalamus.

A 2023 study in mice showed that genetic control of insulin production by the choroid plexus could change food intake. The hypothalamus was rewired by changing choroid plexus insulin levels. Insulin released from here suppressed appetite.

Another source of insulin in the brain also reduces food intake. A 2022 found that insulin producing neurons at the back of the brain, called the hindbrain, reduced food intake in mice.

Might help the brain stay healthy as we age

So if brain insulin can change appetite, does it control blood sugar?

No. At least there is no evidence for this currently. It is unlikely this insulin leaves the brain. Therefore, its unlikely to control glucose levels in the same way.

Instead, insulin in the brain might help the brain stay healthy as we age. For example, Alzheimer’s disease is often, unofficially, termed type 3 diabetes. This is because the brain is insulin resistant in Alzheimer’s. It cannot properly use glucose either.

This is a big problem. Glucose is the main fuel for the brain. In fact, estimates suggest there is a 20% energy gap in Alzheimer’s. Even without brain cell loss, this alone will impair cognitive performance.

This has led to attempts to boost brain insulin. Spraying insulin into the nose can improve cognitive performance in Alzheimer’s, in some, but not all studies.

Brain glucose use also decreases over time and intranasal insulin also seems to limit this decrease.

Therefore, is more brain insulin always a good thing?

Not necessarily. In women specifically, higher levels of insulin in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with poorer cognitive performance.

There is still much to learn about brain insulin production. For example, which insulin source came first? The brain or the beta cell? Hopefully it doesn’t take another 30 years to find out.

But given the strength of evidence of brain insulin production, it won’t be long until our school textbooks are updated.

Read more about the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge project led by Dr Craig Beall and Dr Thomas Piers that looks at how to make use of brain insulin production to improve beta cell therapies.

What are beta cell therapies, and do they offer hope for a cure for type 1 diabetes?

April 15, 2025

Clinical trials in beta cell replacement are creating a buzz among the diabetes community. We explain what beta cell therapies are, how close they could be to becoming a potential treatment option, and how Grand Challenge research is helping bring them closer to the reality.

In type 1 diabetes, the immune system attacks the beta cells in the pancreas, which make insulin. Insulin is essential for regulating our blood sugar levels. So people with type 1 have to check blood sugar and take insulin multiple times a day, every day, to stay alive.

For many people, the advances in diabetes technologies mean that some of this constant checking and dosing can now be done automatically by continuous glucose monitoring and hybrid closed loop systems. However, even the latest tech cannot get close to mimicking the body’s finely tuned system for keeping glucose in check.

One of the most promising routes to a cure for type 1 diabetes is to seek ways to replace the lost beta cells and restore insulin production. We know it can work – the first successful human transplants of beta cells taken from a donor happened as far back as 1990.

The parts of the pancreas that contain beta cells are known as islets. In 2008, the UK launched an islet transplant programme for people with type 1 diabetes who experience frequent life-threatening episodes of low blood sugars (severe hypoglycaemia, or ‘hypos’) but have no awareness of the warning signs. It was an exciting advance, offering the hope of freedom from insulin therapy for some.

Islet transplants are limited

While islet transplants are pretty effective at giving people more stable blood sugar levels and cutting episodes of dangerous lows, there are several reasons why they’re not widely suitable as a treatment for type 1:

- Data suggests that an average of 3 donor pancreases are needed for 1 successful transplant. Donor organs are sourced from deceased individuals and – like most transplant programmes – the demand severely outweighs the supply of usable tissue.

- Transplants from a donor may be rejected by the body, so recipients must take lifelong medication to suppress their immune system (immunosuppressants). This leaves people compromised – at greater risk of certain cancers and severe infections.

- Despite immunosuppression, transplanted islets often fail to survive in the long term because they can’t get the oxygen and nutrients they need.

- While they can allow some people to temporarily stop insulin therapy, this is rarely permanent. Over time, most people will need insulin again, although usually at lower doses.

Fewer than 350 islet cell transplants took place in the UK between 2008 and 2022. There’s an urgent need to find effective and sustainable alternative approaches to beta cell replacement that can be accessed by many more people with type 1. That’s why beta cell replacement is one of the three major research themes of the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge.

Exciting trials underway

Some of the most talked-about research happening in type 1 diabetes right now are clinical trials in beta cell replacement.

One trial, led by a company called Vertex, is testing transplants of beta cells grown in the lab. The results have been really promising, with some participants no longer needing insulin. However, they still need powerful immunosuppressants to prevent rejection. The treatment is now in the final phase of testing, and if all goes well, Vertex plans to seek global approval in 2026. It’s likely this would initially only be for people who experience frequent severe hypos and have no hypo awareness.

In October 2024, Chinese researchers reported positive results using beta cells grown from a patient’s own stem cells. It’s very early days – they only tested it in one person – but this approach has potential to overcome the rejection problem because the transplanted cells would be recognised as ‘self’.

Another first-in-human study was reported by Sana Biotechnology at the start of 2025. They used donor beta cells but gene-edited them to become invisible to the immune system. After four weeks the transplanted cells had avoided immune attack and were producing insulin.

The bigger picture

Type 1 diabetes is complex and we’re unlikely to land on a one-size-fits-all cure. So, while the current trials are hotly anticipated, they’re only one part of the story. And that’s why the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge is funding over £16 million into 10 research projects looking at building better beta cells for transplantation, protecting beta cells during and after transplantation and regrowing beta cells in people with type 1 diabetes.

Nearly two decades after the islet transplant programme launched in the UK, we’re getting closer to better beta cell replacement therapies. And the Grand Challenge is helping to push the pace of progress so that more people can be released from the daily burden and dangerous complications of type 1 diabetes.

You may also be interested in

From discovery to innovation: 103 years of insulin progress

March 4, 2025

11 January 2025 marked exactly 103 years since insulin was first given to a person with type 1 diabetes, a 14-year-old boy called Leonard Thompson. At the time, a type 1 diagnosis was a death sentence and before receiving insulin, Leonard Thompson’s blood sugar levels were dangerously high.

The history of insulin is one of scientific breakthroughs, perseverance, and innovation.

Banting and Best’s breakthrough

The breakthroughs began in 1921 when Canadian researchers Frederick Banting and Charles Best discovered that the hormone insulin could control blood sugar levels and was essential for our body to make and use energy. This discovery was a turning point for people with type 1 diabetes, as it became clear that supplying the insulin they need could be life-saving.

Banting, Best, and their colleague John Macleod were able to extract insulin from the pancreas of dogs but needed the help of biochemist James Collip in purifying the insulin so it would be safe enough to be tested in humans. In December 1921, a more concentrated and pure form of insulin was developed, this time from the pancreases of cattle.

Evolution of insulin extraction

The production of insulin, initially from animal pancreases, became more widespread in the following years, marking the beginning of modern type 1 diabetes management. By late 1923, insulin was commercially available, and people with type 1 diabetes could live longer, healthier lives with effective treatment.

In the decades that followed, innovations continued. In the 1970s, synthetic human insulin produced using bacteria cells replaced insulin from animal sources. This allowed for a more consistent and efficient supply of insulin. The 1980s saw the development of long-acting and rapid-acting insulins, improving control over blood sugar levels.

Innovations in insulin

Research into insulin has continued to evolve. Recent advancements have led to better ways of taking insulin, with the creation of insulin pumps and hybrid closed loop technologies that can help give people with type 1 diabetes the amount of insulin they need automatically and more precisely. Insulin remains the backbone of type 1 diabetes management today with everyone living with type 1 still relying on insulin to manage their condition, just like Leonard Thomson in 1922. Although we’ve come a long way since then, insulin treatment remains difficult and demanding. Insulins need to be easier, smarter and safer.

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge and novel insulins

To get there, the Grand Challenge is funding researchers to continue to write the story of insulin. They’re working to design new types that will work quicker and more precisely, often called novel insulins.

We’ve invested £2.7 million so far to fast-track discoveries in three different avenues:

- Ultra-rapid insulins that would respond more quickly to rising blood sugars, reducing spikes and bringing a fully closed loop system closer.

- ‘Smart’ glucose-responsive insulins would activate when blood sugar levels are high and deactivate when it drops too low. This could make insulin management more automatic, reducing the constant need for calculations or frequent injections and reducing the risk of lows and highs.

- Combining insulin with another hormone that raises blood sugar levels.

This could give people more stable levels, making daily management easier and more effective. Ultimately, the goal is to make insulin treatment feel less like a full-time job and more like something that works in the background – giving people with type 1 diabetes more freedom and better health.

You can find out more about these projects in the ‘Novel Insulins Innovation Incubator’ section of our funded projects page.

The Grand Challenge community – “Work differently, work collaboratively, work swiftly”

December 4, 2024

In November, we hosted our Beta Cell Therapy and Root Causes Symposium, uniting the rapidly growing Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge community. More than 100 researchers, people with lived experience of type 1 diabetes, and collaborators came together for the first time. It was a space to share progress and fresh ideas, and to explore new collaborative opportunities, leveraging the diverse expertise within the community. Importantly, we also got to hear how people affected by type 1 diabetes have been working with research teams to ensure the discoveries and treatments scientists pursue are grounded in their needs.

Dr Mirjam Eiswirth, who lives with type 1 diabetes and leads the Patient and Public Involvement activities for Prof Shareen Forbes and Dr Lisa White’s project, was one of our speakers. Here, she shares her thoughts on the symposium.

“£50 million – that’s the incredible amount of money that the Steve Morgan Foundation has dedicated to the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge towards the race for a cure. It’s a marathon, not a sprint, but as we heard at the Symposium – we’re well on track.”

Mirjam speaking at the symposium

A meeting of minds

107 experts from 27 institutes across 8 countries and nations gathered in London for the first time to focus on two of the Grand Challenge’s strands:

- Root causes of type 1 diabetes: what is it that makes the immune system attack the pancreas, and how can we stop this?

- Replacing beta cells: once the beta cells have been destroyed, how can we replace them with new, functioning ones to give the body a chance to make insulin again?

Can we restore insulin production in the body?

We heard about innovative approaches Grand Challenge researchers are exploring to make beta cell transplants better, more efficient, and have fewer side effects. Or to even help existing healthy pancreatic cells morph into beta cells, so that the body can produce its own insulin again. Because, as Sarah Gatward, one of the experts by experience, so neatly put it: “Nothing can control blood glucose better than beta cells.”

Could we stop type 1 diabetes from developing?

The second key theme was understanding what happens in the body that makes it turn against itself and destroy beta cells in type 1 diabetes. If we could stop this immune attack early and protect the beta cells, we could potentially stop type 1 diabetes from developing at all.

Grand Challenge teams told us about the innovative ways they’re hoping to do this, and some of the challenges to tackle along the way. We’d need to catch people early on the path to type 1 diabetes, which means we need good ways to screen for it. And we’d need to make sure we only stop the specific immune reaction at the root of type 1 diabetes, rather than suppressing the whole immune system.

Putting people with lived experience at the centre of the Grand Challenge

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge models the collaborative and disruptive spirit it champions: By including people with the lived experience from the get-go and every step on the way.

Several experts by experience, including myself, gave updates on the different ways we’re getting involved, including reviewing research proposals, as patient and public involvement co-investigators, and as sounding boards when it comes to the applicability of any novel therapy the scientists develop. Because we can ask those uncomfortable “so what” questions or say, “this therapy only makes sense to me if it helps me for more than a year or two – it needs to be a proper cure”.

For the researchers in the room, hearing more about our involvement, perspectives, and why they matter was invaluable. Dr Craig Beall, lead researcher, said: “Hearing the voices of experts by experience was inspirational and at times emotional.”

Anonymous feedback also reflected this:

Expert by experience: “I felt I was able to help inform researchers and others of what their research means to those living with type 1 diabetes and I feel confident that my input has been taken on board and will be used to influence what they do and how they present their research. ”

Early-career researcher: “I met several experts by experience and it really hammered home the importance of our research. I was astounded by the incredible role experts by experience played in shaping grant applications and steering research objectives.”

Experts by experience talking about involving people living with type 1 diabetes at the symposium

Many perspectives, lively debates

Senior researchers, early career researchers, and not least people with lived experience of type 1 diabetes shared their thoughts, hopes and projects related to the Grand Challenge. What unites us all is the vision of creating a world where diabetes can do no harm – and to be creative, think out of the box, work collaboratively, and work swiftly.

One researcher summed it up: “It felt like a community, which was great.”

Delegates chatting at the symposium

Looking ahead

Personally, I am very excited about the progress we’ll make through these research projects. They have the potential to change the lives of millions of people with type 1 diabetes for the better. A cure is still years, if not decades away – the journey to breakthroughs is a long and complex one. We need to move from discoveries in the lab, to testing new treatments with people in clinical trials, to ensuring widespread access to cures. But it’s a path filled with incredible moments of innovation and hope. And I find myself just as excited for the journey as the destination.

Researchers, practitioners and experts by experience working closely together, driven by shared ambition, can really make a difference.

You may also be interested in

What are immunotherapies, and why are people excited about them?

October 8, 2024

Treatments that target the immune system, known as immunotherapies, are emerging to tackle type 1 diabetes. In this blog, we explain what they are and their potential to make a life-changing difference for some people affected by type 1 diabetes. We also introduce two research projects that we’re funding in the UK that are looking at interesting immunotherapy approaches.

The trouble with treatment

Type 1 diabetes occurs when the immune system destroys the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. For over a century, the treatment of type 1 diabetes has centred on replacing the insulin the person can no longer produce. But lifelong insulin treatment can only address the symptoms and keep complications of type 1 diabetes at bay. It doesn’t address the underlying root cause of the condition.

Teplizumab – what’s the big deal?

In November 2022, drug regulators in the US approved the use of a medicine called teplizumab. The news was greeted with huge excitement by experts, who described it as ‘monumental’ for type 1 diabetes. But what’s so special about it?

Teplizumab is the first approved drug to tackle the root of the problem. In a landmark clinical trial, a two-week course of teplizumab was found to slow the immune attack on beta cells and preserve insulin production for an average of three years in people with early-stage or presymptomatic type 1 diabetes. At this point type 1 hasn’t fully developed – the immune attack has begun but there are still enough beta cells to produce some insulin, and the symptoms of type 1 haven’t yet developed.

Delaying the development of type 1 diabetes means more years without insulin injections, constant blood sugar monitoring and carb counting. It can also reduce the risk of developing diabetes complications.

And this is just the start.

How do immunotherapies work?

Medicines that work by interacting with parts of the immune system – known as immunotherapies – have enormous promise for the prevention, treatment and maybe even cure of type 1 diabetes.

Our immune system works by identifying invaders in our bodies – such as bacteria and viruses – and ‘sounding the alarm’ to launch an attack. In this process, immune cells called killer T cells are taught to recognise and destroy the invader.

In people with type 1 diabetes, their immune system mistakenly attacks their own insulin-producing beta cells. Meanwhile, the peacemakers of the immune system – called regulatory T cells, or Tregs – are underpowered against the barrage. Teplizumab works by attaching to a protein on the surface of killer T cells. This stops the T cell from recognising beta cells, effectively hiding them from the immune system to evade attack.

Many more immunotherapies for type 1 diabetes are in the pipeline. Some work in a similar way to teplizumab, whiles others take a different approach, including:

- breaking the vicious cycle of inflammation in the pancreas that usually helps to sustain an immune attack

- boosting Tregs, the natural protectors that can deactivate killer T cells but are in short supply in type 1 diabetes

- neutralising the signals, called autoantibodies, that label beta cells as targets for attack.

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge is funding research into different immunotherapy strategies.

Interleukin-2 (IL-2): Boosting the Tregs

One Grand Challenge project is investigating a way to power up the peacekeeping force of Treg cells, to limit the immune attack on beta cells.

A protein called interleukin-2 (IL-2) is an important nutrient for Tregs and has been tested in clinical trials in people with type 1 diabetes before. The results have been promising but inconsistent..

However, Dr James Pearson has a theory that may explain why the results vary. His team have shown in mice that numbers of Tregs rise and fall in a daily pattern. And he thinks that synching IL-2 treatment with the natural Treg cycle could be crucial for success.

Dr Pearson said: “We’ve seen that there’s a time in mice, in the evening, when the number of Treg cells is at its lowest point in the 24-hour cycle. We think that might be the best time to give IL-2 therapy, because you’re then boosting them back up to a higher level to try to limit activation of the damaging killer T cells.”

They’re testing this theory in blood samples taken in the morning and the evening from volunteers with type 1 diabetes.

IL-2 is already known to be a safe treatment in children and adults. So, if the results from Dr Pearson’s study show a clear potential benefit to timed therapy, then a trial in people with type 1 diabetes could take place.

Abatacept and IL-2 – more than the sum of their parts?

Dr Danijela Tatovic’s Grand Challenge project is also exploring IL-2’s potential, in combination with another immunotherapy called abatacept.

Abatacept is currently used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, another autoimmune condition. It’s been trialled in people with type 1 diabetes where it’s been shown to be able to stop killer T cells attacking beta cells. However, it also weakens the helpful Tregs, which limits its usefulness.

Dr Tatovic is running a small clinical trial in people with type 1. One group will receive abatacept and another group will receive abatacept in combination with IL-2 at different doses and timings. After two months, the research team will see how the different types of immune cells are responding in each group.

Once they’ve established the best combinations of the two drugs, the team can design a larger trial to find out whether the therapy can protect beta cells from destruction and prevent or slow the progression of type 1 diabetes.

Getting closer to a cure

The discovery of insulin in 1921 has enabled countless people to survive and thrive with type 1 diabetes. The approval of teplizumab in the US one hundred years later represents the start of a new era of medicine for people living with and at risk of type 1 diabetes. Immunotherapies hold incredible potential for preventing, slowing down and stopping the destruction of beta cells by the immune system.

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge is also funding research to accelerate progress towards treatments that replace or regenerate the beta cells destroyed by the immune system. And – by combining immunotherapy with promising beta cell therapies – there’s a growing chance of a cure for people who may have never imagined it was possible.

You may also be interested in

The art of research – shaping science in the Grand Challenge

August 29, 2024

People with type 1 diabetes are at the heart of the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge. Their experiences are woven into everything we do, from the design to delivery to dissemination of research.

We spoke to Amelia Skachill Burke, a glass artist from Wales and mum of Ruby who lives with type 1, who works closely with Professor David Hodson, Dr Ildem Akerman, and Dr Johannes Broichhagen’s team, drawing on her family’s experience of the condition, to make sure their research is relevant and accessible to people with type 1 diabetes.

Type 1 diabetes in the family

Amelia’s daughter Ruby was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when she was nine.

Amelia said: “I had some awareness of the condition because we have a family history, but it crept up on us all. After Ruby was diagnosed, it took a few years for us as a family to get a handle on it and her insulin regimes.

“She’s now 16 and gets amazing support from her school and ever-improving diabetes technology like hybrid closed-loop systems. But insulin and technology aren’t cures for type 1.”

Stepping towards science

Amelia said: “I heard about the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge from Professor David Hodson. I approached him about two years ago when I was applying for grant funding from the Arts Council Wales, for my artwork. I wanted to do some background research for my art – to look at islet cells, gain information, gain imagery, things to work from to make glassware inspired by type 1 diabetes.

“He showed me around his offices and labs, and he and the team were so accommodating. We had a lot of conversations, and then he spoke to me about the Grand Challenge. He asked if I wanted to be involved as a PPI (patient and public involvement) co-applicant, and I was more than happy to do anything I can to help.”

Professor David Hodson said:

“Amelia has vast lived experience of type 1 diabetes, but is also a very kind, compassionate, and talented individual. It’s important for us to have someone like Amelia on the research team, to ensure that all aspects of the studies are relatable and relevant to those living with type 1 diabetes.”

From research to reality

Much of the research funded by the Grand Challenge is shaped, supported, and shared by people like Amelia, whose lived experience of type 1 diabetes through Ruby is completely invaluable to our scientists.

Amelia said: “I’m not from a science background, so the goal of my role is to give a realistic view of the research. To make sure the information is accessible to anyone wanting to know what’s being done to help type 1 diabetes.

“Scientific terms need to be well-explained. And when there’s a potential solution or a breakthrough, what’s the real impact it could have on the day-to-day life of someone with type 1?”

Amelia Skachill Burke gives a talk about how she represents beta cells in her art

Bringing science to the studio

Amelia combines her interest in science with her passion of glass art, drawing inspiration from her experiences and the world around her.

Amelia said: “My daughter inspires me. She’s struggled so much with her diabetes and we’ve all struggled together. But we’ve always done it as a family – we never wanted her to feel alone or overwhelmed by it. So anything we could do to support Ruby is what we’ve always done. When the opportunity came for me to bring medicine and art together, it just felt like a no-brainer. I’m inspired by scientific imagery, but at the heart it’s Ruby that inspires me all the way through.

“I think art and research work together – the art explains the research and gives people a visual representation of what’s happening in the world. I’m currently working on a glass interpretation of a pancreas – the pancreas is a very important organ with lots of functions, but only 2% of it is actually made up of beta cells.

“These infinitesimally tiny cells have a huge impact on everyone’s everyday life – they’re like gold dust, and I’m playing with the idea of using gold dust to try to explain the significance of them in my glass art.”

More of Amelia’s artwork

Research through the looking glass

Working closely with Grand Challenge researchers puts Amelia at the cutting edge of type 1 diabetes research. Amelia said: “My hope for the future is a cure. Prof Hodson’s team and lots of other scientists are working on this at a beta cell level, and it would be amazing if we can find a solution where people with type 1 don’t have to rely on technology or insulin. Something that makes their lives easier, whether it comes in the form of medicine or not.

“I’m planning to run some glass workshops as well with kids and teenagers with type 1, to try to expand and explain my artwork and type 1 diabetes research. Anything we can do to shed more light on the condition and research, spread awareness, and support everyone living with type 1 diabetes.”

Professor David Hodson said:

“It’s been an amazing experience to see Amelia turn our microscope images into colourful and tactile artwork installations, which simultaneously represent the beauty and challenges of type 1 diabetes.”

Find out more about our community of people with type 1 who are involved with the Grand Challenge.

Glass art in the kiln

You may also be interested in

Grand Challenge in the community

June 18, 2024

In May, we were out and about at type 1 diabetes community events. First, the virtual peer support platform DiabetesChat held a Grand Challenge special, then members of the Steve Morgan Foundation led a session at the annual Talking About Diabetes event.

DiabetesChat Grand Challenge special

DiabetesChat’s fifth research event was all about the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge. Liam Eaglestone, CEO of the Steve Morgan Foundation (SMF), kicked off with a short presentation about SMF and their £50 million investment in type 1 diabetes research. He explained how the Grand Challenge is disrupting the research landscape and accelerating us towards treatments and cures for type 1.

Panel Discussion

DiabetesChat co-host Mary Murphy chaired a panel discussion between the three Senior Research Fellows, Professor Sarah Richardson, Dr James Cantley and Dr Victoria Salem. Mary asked the researchers questions about the Grand Challenge, including how the partnership is supporting research into future therapies and cures for type 1.

Dr Salem said: “The Grand Challenge has given us the freedom to think disruptively and bring in new ideas from other fields.”

Dr Cantley answered: “This type of research is mission driven, allowing us to take risks to move the field forward, improving lives and finding cures.”

Professor Richardson said: “We are supporting the next generation of researchers and establishing the research infrastructure here in the UK. With fresh brains in the mix, the future is bright!”

Research presentations

Each researcher spoke about their research and the audience were able to ask questions. Dr Cantley explained how he is developing new treatments for type 1, Professor Richardson took us through her research into type 1 immunology, and Dr Salem described how she is creating a protective device for lab-grown beta cells.

Watch the recording of the Grand Challenge DiabetesChat.

Response from the community

Over five hundred people tuned in to the event live, with almost 2,000 watching the recording. One audience member said: “Sarah’s slides with the artwork has made me understand my T1D after almost 60 years of diagnosis. Next life, I want to be a researcher!” Another said: “Amazing insight and I’ve gained a lot of knowledge tonight about my T1D and what the future might hold.”

Tom Dean, who hosts DiabetesChat said: “It was a fabulous, interesting and informative evening and the feedback we have received from the community has been very positive. It has given people hope and great anticipation for a healthier future for us all.”

SMF at Talking About Diabetes

The Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge had a big presence at this year’s Talking About Diabetes (TAD) event in Liverpool, with members of Diabetes UK, JDRF UK and SMF all in attendance, both on and off the stage.

Photo of Liam (left) and Jack (right), courtesy of Marc Lungley.

Liam and Jack Eaglestone

Liam and his son Jack were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes just one year apart. The pair gave a joint talk at this year’s TAD event where they praised the advances in technology and those championing access to it. Both Liam and Jack use hybrid closed loop systems to manage their type 1. They shared how the system has helped stabilise their blood glucose levels, reduce diabetes burnout and improve their sleep.

Jack said: “I used to have to take around one day a week off school because my blood glucose levels were so unstable. I would have repeated hypos which made me fall unconscious, high ketones and vomiting. Then, hybrid closed loop made that all disappear. It was like a miracle.”

Liam added: “Technology is great – but it is not a cure. The Grand Challenge is seeking that cure, by bringing together some of the best and brightest brains in the type 1 research community.”

A message from Steve and Sally Morgan

Steve and Sally Morgan couldn’t be at TAD in person, so they shared a video sharing their personal connection to type 1 through Sally’s son, Hugo, which led to the SMF’s transformational £50 million investment in type 1 diabetes research.

Watch the video from the Morgans below.

You may also be interested in

What it’s like being an expert by experience in the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge

May 31, 2024

David Mitchell lives with type 1 diabetes and is a member of the expert funding panel guiding the projects we will fund through the Novel Insulins challenge. Here, he explains his volunteer role on the panel, the importance of involving people with lived experience in research, and what he learnt from the experience.

The Grand Challenge has committed £15 million of funding for researchers to design the next generation of insulins to make managing type 1 diabetes less challenging. To ensure we fund the most promising projects that offer the most potential benefit for people with type 1, we asked researchers to pitch their project ideas to a panel of experts. In this blog, David shares his experience of being a lived experience member of this panel.

Novel insulins pitches

It was a privilege being part of the international panel of experts for the Novel Insulins Innovation Incubator, reviewing grant applications of up to £500,000. It was fascinating to hear the exciting ideas that the researchers presented to us. All the research ideas had a lot of viability behind them already – my role was to provide a lived experience voice to help maximise the projects’ impact on people with type 1.

Insights on living with type 1

I gave the researchers perspective on the day-to-day things I experience with type 1. While some aspects are relatively well understood, I can relay little quirks to people who don’t live with the condition. For example, I asked the researchers pitching their projects to explain how their new ideas for insulin would consider the varying levels of daily activities not just between individuals but in the same person on different days.

Some of the applicants provided more detail than others on how they would factor exercise into their designs, which helped us evaluate the projects. Encouraging the researchers and other panel members to think about the daily reality of life with type 1 and how that affects science is why it is so important to involve people with lived experience in research right from the start.

Drawing inspiration from other industries

This volunteer role is very different from my career working at a financial technology (fintech) company. In that industry, we approach things from a different position to traditional corporate companies, so I’ve been able to suggest alternative ways of doing things. For example, we bring people together in big ‘hackathon’ events, which foster collaborative problem-solving over a short space of time. There’s no reason this concept couldn’t be taken into the research lab. This made me feel like, as well as relaying my experiences, I was also adding value to the development of the science.

Giving hope to people with type 1

As a member of the panel, I learnt a lot about type 1 diabetes research. I heard how insulin treatment could be enhanced to take away the need to constantly pump more insulin in and could be simplified to just one injection a day or even a week. Throughout the day, I learnt about different ideas for insulins that reduce the risk of hypos – a reality people with type 1 like me have to deal with.

When you live with the daily grind of constant insulin injections and glucose monitoring, the possibility that these insulins could be developed and allow you to forget about type 1 for the day is fabulous. Some trials of novel insulins are ongoing in animals. Learning that research is happening at this level gives me hope this could translate to something meaningful for humans.

The Grand Challenge approaches research differently

The amount of money the Grand Challenge is investing in type 1 diabetes research is fantastic. Being a panel member opened my eyes to how this injection of funding will lead to amazing research and accelerate developments. The substantial funding means scientists aren’t just working on a concept, it’s taking those ideas forward to unlock real progress and new treatments. It also attracts the interest of top experts from around the world to build on their amazing existing work.

I saw how the approach the Grand Challenge takes is different to typical research funding, which can be a long process. The Grand Challenge is structured to ensure that research ideas are turned into real action and meaningful change as soon as possible, while maintaining the scientific rigor.

Together Type 1 Young Leaders at DUKPC

May 28, 2024

In April, we were delighted to be joined at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference by seven Young Leaders from the Together Type 1 programme. With funding from the Steve Morgan Foundation, the UK-wide programme aims to bring together young people aged 11-25 years with type 1 diabetes, providing them with a platform to build confidence, learn new skills, and meet others in their region living with the condition.

The Young Leaders had a very busy schedule during the conference, attending key scientific sessions, interviewing Grand Challenge researchers, and sharing their own lived experience of type 1 diabetes with scientists and healthcare professionals alike. We’re grateful to two of them for taking the time to write about their first DUKPC experience.

Young Leader Elise Featherstone from the North team shared her reflections:

“A key presence at this year’s conference was the Type 1 Grand Challenge. Hearing about this research programme made me consider, for the first time, the reality of not having type 1 diabetes for the rest of my life. A cure may be sooner than we think, and it may well be because of the Grand Challenge!”

Bringing back beta cells

Dr James Cantley, a Grand Challenge Senior Research Fellow, optimistically shared findings from his team who are working to grow back insulin-making beta cells directly in the pancreas. Even during its early stages, this research offers hope and optimism for the diabetes community that one day we will be able to have functioning beta cells again.

New homes for transplanted cells

Dr Vicky Salem and Rea Tresa highlighted their lab’s work on bio-printing a protective housing unit to protect the life-saving transplanted beta cells. This project aims to make sure that new beta cells placed in the body are able to thrive and adapt. The Grand Challenge’s ability to bring great people and cutting-edge innovations together to accelerate life changing research is very exciting.

The type 1 timeline

Professor Sarah Richardson explained that as well as a cure for people with type 1 diabetes, we also need ways to prevent the condition from ever occurring in people at high risk. Prof Richardson shared her team’s work looking into rare pancreas samples. Obtaining these samples is difficult but has enabled Prof Richardson and her team to learn more around the type 1 diabetes timeline and how we may be able to prevent or intercept the immune system attack in type 1. Such a breakthrough could completely alter the implications of diabetes on society, our healthcare system, and end type 1 altogether for future generations.

Next Amelia Trencher from the Midlands and Eastern team summed up her thoughts:

“It was so wonderful to have the opportunity to attend DUKPC 2024 as a Young Leader, and to be able to have conversations with people who really wanted to hear about our experiences as young people living with type 1 diabetes.”

Scientific sessions

The collaboration between Together Type 1 and the Grand Challenge was a real highlight for all of us Young Leaders. I really enjoyed hearing the researcher I interviewed talk about his work and the impact he hoped it would have.

The main session about the Grand Challenge was really insightful and made us feel positive looking towards the future of life with type 1 diabetes. The main takeaways for me were that the big focus at the moment is on developing ways to give people with type 1 new beta cells, which seems to be very promising, moving towards a potential cure for type 1 in the reachable future.

Some researchers also talked about how they can use lessons learned from research into cancer and apply that to the diabetes research, which was very interesting to hear. It was also emphasised how important funding is for these projects.

Building networks

The Young Leaders were so pleased to meet Steve and Sally Morgan and to chat about how we have each benefited from being part of the Together Type 1 programme so far, and it was really lovely to see how much they cared about the personal impact of the programme of the lives of Young Leaders, not just the achievements and events that have taken place.

We also got to spend time with others who have lived experience of diabetes, and really enjoyed our joint session with the Dedoc voices, an international group diabetes advocates. It was also brilliant to just spend time with the other Young Leaders, as we had never met before, and by the end of the few days it felt like we’d been friends for ages.

The importance of the patient voice

On the second day, I was part of a panel discussion session about the first year of care for young people with diabetes. Not only was it such an honour to share the panel with some really inspiring people, but I also loved being able to have conversations during and after the session about the potential barriers for young people receiving optimal care.

I also had conversations with people about the mental burden of type 1 diabetes, including technology, which isn’t always considered by healthcare professionals, and can definitely be a barrier to optimal care.

Across the three days, I was so happy to see how engaged healthcare professionals were when talking to us about ways things could be improved in clinic, as well as realising how valuable our contributions can be in developing resources and programmes for other young people with type 1 diabetes.

In the future, I would love to see even more of a presence of young people at conferences, and in other spaces like DUKPC, and for more opportunities to meet and talk to researchers about their work, as this is something we don’t often get to do!

We’re grateful to Elise and Amelia for sharing what they did and learned while they were at DUKPC. It’s clear the Grand Challenge offers fresh hope to people living with type 1 diabetes.

You may also be interested in

“It’s an optimistic time for people with type 1” – Morgan Shaw, a Grand Challenge researcher who has type 1

February 1, 2024

Research Technician Morgan Shaw has type 1 diabetes and is working in Dr James Cantley’s lab at the University of Dundee, which is funded by his Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge Senior Research Fellowship. Morgan tells us how collaboration, ambition and people with type 1 are at the heart of the Grand Challenge.

My type 1 diabetes

I was diagnosed with type 1 when I was 14, just before my first GCSE exam. My Dad researches type 1 diabetes and my mum lives with type 1, so they caught my symptoms of weight loss and extreme thirst before any permanent damage was caused. I’m currently using a closed loop system to manage my type 1 and I really like it. The system reduces the burden of type 1 and the variability in my blood glucose levels. This technology means I can get on with my day and work as anyone else would except for having a can of cola on my desk. The pump has also made my condition less visible to my colleagues as I don’t have to treat my hypos as often or give myself insulin injections.

Helping others with type 1

I’ve always been interested in science. At first, I wanted to be a vet, but having my own medical conditions pushed me to human science and helping other patients. I really enjoy being a lab technician because it’s a more hands-on approach to science. I like working with my hands and having a routine in the lab. Despite not being in direct contact with patients, I still have a sense that I’m helping other people living with type 1.

Giving our research perspective

Having diabetes and working on a type 1 specific project is really exciting. It gives me a different view and helps me focus on what people with type 1 need and want. It also helps me motivate the research team during long, hard lab days because knowing the end goal pushes us through. As a biomedical research lab, working with cells, tissues and models, we can feel separate from patients but having my perspective helps us. For example, I help scientists who aren’t used to speaking directly to people with type 1 to make sure the language they use in their presentations has the sensitivity and best phrasing for people with diabetes to read.

Teamwork in the Grand Challenge

I love working with the team in Dr James Cantley’s lab. We have lots of collaborators with different expertise working on different projects, so I get to see the other research taking place. We have lab meetings every week and scientific journal clubs to discuss newly published research papers. The Grand Challenge has a really collaborative feel, and we’re invited to attend a variety of different meetings. I’ve been given lots of responsibility as a technician and treated the same as the postdoctoral researchers, which isn’t always the case in other labs. James appreciates that we need a range of people with a variety of diverse opinions to achieve the most success.

Boosting Scottish diabetes research

It’s great to see a Northern lab in the UK being recognised by the Grand Challenge and receiving this funding. I wanted to work in Scotland and have been following James Cantley’s research closely. In my previous lab, I gained experience processing and studying human pancreatic organs generously donated for diabetes research. In James’ lab, we use a range of different cell and tissue approaches to progress our research, which means we can work faster and more flexibly towards new treatments.

Regrowing a person’s own beta cells

We’re studying pancreatic cell types which don’t make insulin to explore whether these can be converted into insulin-producing cells in people with type 1. The lab is exploring how the insulin-producing beta cells are related in embryos to another pancreatic cell type – the ductal cell. Dr Lisa Logie (a postdoctoral researcher) and I are optimising ductal cell isolation and culture, before other scientists in our team will add different drugs to see if they can transform them into beta cells.

A great research opportunity

I was following the Type 1 Diabetes Grand Challenge before I started working in James’ lab. It’s a very exciting time for type 1 diabetes research. The unprecedented amount of funding very generously invested by the Steve Morgan Foundation is making science a lot more open and available to more people. Being an early career researcher, working on this high-profile project is a great opportunity for me to learn new techniques and become more specialised. I’ll be working on this research project for its five-year duration. This gives me job security and the chance to focus and commit to this one project, which is very unusual in academic research.

A cure for type 1 diabetes

No one person with type 1 is the same as another, so we need to make sure there are treatment options for everyone. To me, a real cure for type 1 would be not having to administer insulin or wear a pump. I want to have a normal experience of life without having to think about type 1 with every aspect of my day.

Developing a cure for type 1 is the goal, but in the short-term, we need to keep making progress towards better quality of life for people with type 1. Making inulin pumps more sensitive and reducing the amount of insulin needed would be helpful, which is where the novel insulins strand of the Grand Challenge comes in.

Five-year research plan

Over the next five years it will be important to test different ideas, to evaluate which work and which don’t so that we can adapt our thinking and move forward towards our goal. Our aim is to develop a new treatment concept for type 1 by the end of the current Grand Challenge Fellowship, which we hope will then progress toward clinical trials.